I WROTE SEVERAL false starts for this blog over the last (eek!?) two months, but never had time to finish and post them. The futher behind I fell, the more I wanted to say to catch up. Eventually I figured out that just wasn’t going to be possible, and have elected to move on.

While this blog includes news, I can only write erratically and thus my news is rarely timely. I try to mention big events like conventions, major projects, interviews, maybe games I’m playing or what the dogs are doing, but I think the best posts I write are reflective, touching on several related topics and how they intersect with my work.

While this blog includes news, I can only write erratically and thus my news is rarely timely. I try to mention big events like conventions, major projects, interviews, maybe games I’m playing or what the dogs are doing, but I think the best posts I write are reflective, touching on several related topics and how they intersect with my work.

Think of this as an entry in my occasional series of “Pictures Have Stories” essays, because I’m going to tell you … in roundabout due course … about the painting “Catch An Elusive Scent” that I did for ICE’s Middle Earth card game. There are a few stops along the way.

Recently a library patron turned in the unabridged audio CD of a fairly new book called Hallucinations. It grabbed my attention when I noticed it was by neurologist and medical-science popularist Oliver Sacks. If you haven’t heard of him or read any of his books, and if you have the slightest interest in the workings of the human brain and mind (diseased or hale), then you’re in for a treat once you get ahold of his works.

The key thrust of this particular book is the variety of, and how incredibly widespread and even common are the visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and other misperceptions our brains can toss our way. Yet the stigma about hallucinatory experiences is so profound that sane, healthy researchers were hospitalized and misdiagnosed with schizophrenia, for example, with absolutely no other reported symptom than telling doctors they heard voices. Still, people are aware that amputees frequently experience phantom limbs, and the “waking nightmare” of sleep paralysis with the vision of a gigantic spider on the ceiling, or the wide-awake glimpse of a beloved pet returning after death draws nods of recognition among many.

The key thrust of this particular book is the variety of, and how incredibly widespread and even common are the visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and other misperceptions our brains can toss our way. Yet the stigma about hallucinatory experiences is so profound that sane, healthy researchers were hospitalized and misdiagnosed with schizophrenia, for example, with absolutely no other reported symptom than telling doctors they heard voices. Still, people are aware that amputees frequently experience phantom limbs, and the “waking nightmare” of sleep paralysis with the vision of a gigantic spider on the ceiling, or the wide-awake glimpse of a beloved pet returning after death draws nods of recognition among many.

Now consider having those kinds of phantasms broadened out and multiplied across a sizeable swathe of the population who, until recently, had no recourse to researchers using EEGs and MRI brain scans to track what is happening inside the skull, much less the specificity of brain surgery and the necessary electro-stimulation mapping preparatory to excise lesions, abcesses, or an intractable epileptic locus. And it was in reading about these that I found the “shock of recognition” much more profound.

Things people see (or otherwise perceive) on a regular basis are often the beings who populate the world of the fantastic. Wee folk, interpretable as fairies and gnomes. Giants, all proportionate in defiance of the square-cube laws of physics. A secret world perceptible with second sight. The breathtakingly beautiful Seelie and the devasatingly foul Unseelie. Craggy ogres with distorted noses and teeth like a field of tombstones. Ghosts and dopplegangers. Demons and angels. Heaven and hell. The ecstacy of seers, mystics, and saints, and the worldwide use of psychoactive drugs and trance states to achieve transcendent visions of the sacred. All these are among the common forms of externally-perceived phantasms of the mind absent mental disorders — typically, the person recognizes these as hallucinations. Often these misperceptions accompany physiological stresses ranging from blindness to epilepsy, migraines, stroke and beyond, but by no means is this a requirement to having such hallucinations.

I don’t think I’ve felt such a shift of insight so profound in decades. Sacks handles the delicate questions of myth and religion with respect, but for the purposes of this essay, I bring up the book in the context of my life as an artist/writer, and a consumer of the fantasy genre in all its manifestations.

HYPNOPOMPIC HALLUCINATION

I suspect it is impossible to read the book without thinking “Something like that happened to me once!” I remembered a few events in my past as I listened to the book, things I hadn’t thought about in many years. The relatively short but intense olfactory hallucination of a friend’s distinctive cologne as I sat in class at university. The eyes in the closet when I was very young, my childhood version of the monster under the bed. The “return” of my first cat after she died of feline leukemia, back before there was a vaccine to prevent it.

I knew the term “hypnagogic” from reading books on sleep research. (I highly recommend Dreamland: Adventures in the Strange Science of Sleep by David K. Randall.) The term references the twilight time as you are falling asleep. “Hypnopompic,” a term new to me, describes the exit from slumber, that transitional phase between sleep and wakefulness. I’ve long found many of my best ideas, scraps of dialog, artistic concepts, and other moments of clarity arrive full-blown in a hynopompic state, which I mentioned in a recent and lengthy interview in the German Obskures blog. (That entry is all in English.)

I knew the term “hypnagogic” from reading books on sleep research. (I highly recommend Dreamland: Adventures in the Strange Science of Sleep by David K. Randall.) The term references the twilight time as you are falling asleep. “Hypnopompic,” a term new to me, describes the exit from slumber, that transitional phase between sleep and wakefulness. I’ve long found many of my best ideas, scraps of dialog, artistic concepts, and other moments of clarity arrive full-blown in a hynopompic state, which I mentioned in a recent and lengthy interview in the German Obskures blog. (That entry is all in English.)

Unquestionably a response to the suggestibility of my mind while reading Hallucinations, I had a hynopompic hallucination just two mornings ago. The good news was that I almost immediately knew exactly what had just happened, and in consequence it more delighted than alarmed me. Out of context, it would certainly have utterly freaked me out.

The “almost immediately” is telling: waking up to discover that one’s pillow is a green sac of pus and pestilential gangrene, shoving it away in horror — that would be unutterably ghastly without having a context. The impression was no dream, because my eyes were open, and it was utterly convincing. I would have wondered what was wrong in my head, what psychological quirk would have possibly raised up such a disgusting perception, except that Sacks remarks how often certain hallucinations have little or no relationship to one’s psychology or current events in one’s life. Thanks to the contextualizing frame of Sacks’ book, I didn’t have cause to doubt my sanity and of course, the pillow looked perfectly normal half a second later. (And I find it hilarious that the publisher’s tagline about Dreamland is, “You’ll never look at your pillow the same way again.”)

ANOTHER HALLUCINATION

As I said, the experience amused me, but it also kickstarted the memory of another occasion when I had been “seeing things” — and here comes the connection to my artwork. In my early twenties, I recall being rather sick and running a fever at which time I saw a man in a science fictional-style jumpsuit in my room. He had an open space helmet but no face, despite the rest of his head being evident inside the helmet. It was as if someone had used an ice cream scoop to carve off the visage. It didn’t seem to bother him as he stood there, looking around until fading away some moments later.

It was such a striking image that, once I got better, I drew and inked the piece, and it promptly sold at the next convention I attended. People told me how creepy it was, and I completely agreed. (I have no copy of the piece but remember it well.)

ELUSIVE IMAGERY

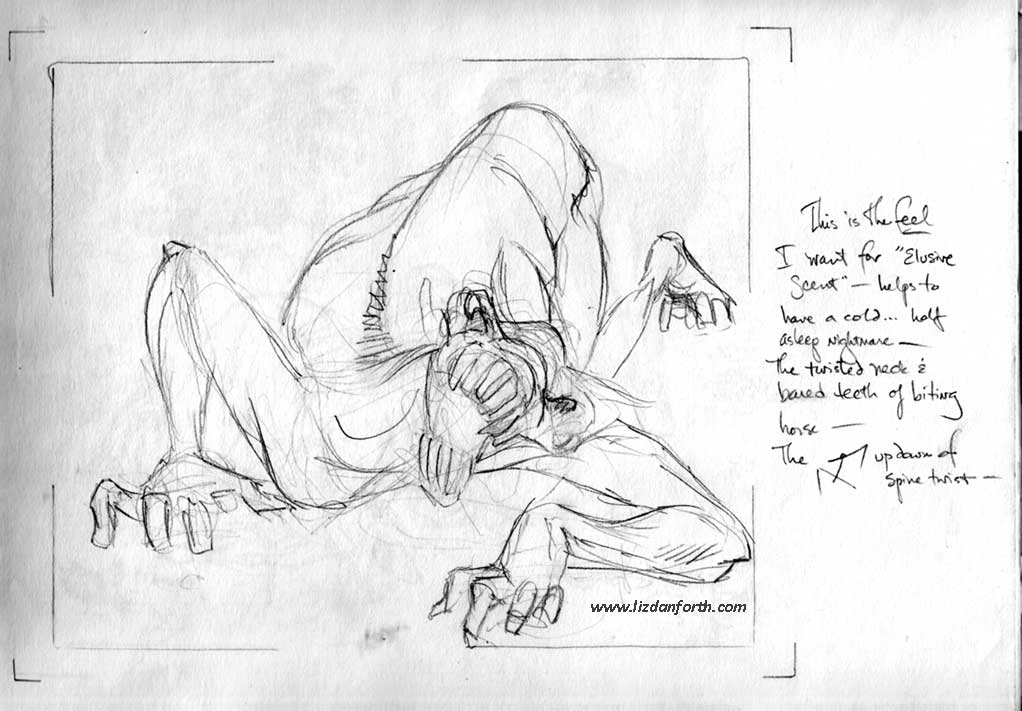

That experience never repeated itself until 1997. I recall working hard to meet crushing deadlines when I came down with a cold, accompanied by a fever. Accepting the inevitability that I couldn’t work when I was that sick, I went to lie down in the midafternoon, neither awake nor asleep, but with my mind still flailing about.

The current assignment on my agenda was “Catch an Elusive Scent” for Iron Crown’s Middle Earth collectible card game, “The Lidless Eye” expansion. The illustration was for that moment when one of the Black Riders comes sniffing around for the hobbits who have only just left The Shire. I wanted to catch the encroaching sense of dread, the fear of the unknown, and the sheer creepiness of that scene, but the ideas I’d come up with were going nowhere.

Then as I lay on the bed, I felt as if my body were twisting, and saw a form take shape in my field of vision that mirrored the bonecrack distortion I was feeling. Sick or not, I got up and went to my art table to catch that impression before crawling back in bed.

This is what I drew.

When I returned to the art table ready to work a day or two later, the vividness of the image had not faded but now I could see the particulars were not useful. No Nazgûl has horse’s teeth, and the viewer wasn’t the one being sniffed about for. In fact, the faceless space jockey of years before suggested the cloak’s empty hood, which fit the Tolkien canon in any case.

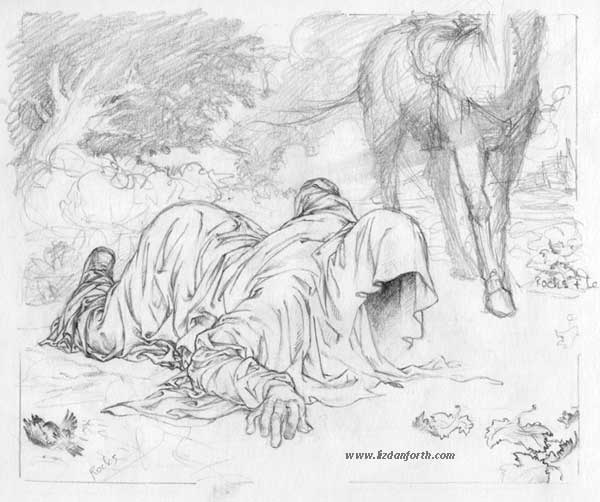

The next page in my sketchbook has this image.

This picture is much more polished and refined, and considerably less scary. Still, I think it retains a bit of the unsettling creepiness of my original idea, and it was a popular image that sold regularly amongst my prints for a time.

PROJECTIONS AND PHANTASMS

In neither the case of the space jockey nor the body-distorted proto-Nazgûl can I perfectly recall if the images were only in my mind’s eye or projected into external space. Certainly, they were more fully formed than simple imaginings, more than the kind of mental camerawork I do to discover the right point of view from which to start a sketch. That is why I refer to them with the highly suspect term “hallucination” and also because I’m coming to this subject from the perspective of recently reading a book of that title.

And I will leave the subject there. I don’t usually “see” things no one else sees except as every writer or artist imagines something before bringing it alive. Even the most hallucinatory image I ever yet created (below) was conscious and purposeful, the deliberate embodiment of an emotion and not of any particular vision.

I am not one to believe in supernatural nor preternatural explanations when more mundane understandings suffice, so I genuinely find it a source of wonder and of compelling fascination to glimpse how the hardwiring (and sometimes the misfiring) in the human brain has likely been the genesis of the many beings of fantasy, in the absence of any external tangible reality of such creatures. It may sound peculiar for me to say this, but as an artist regularly asked to depict such beings, both monstrous and beautiful, knowing this carries a kind of transcendent delight. It is as if I have been shown the gate at the bottom of the garden, and am free to explore the Lands of Other in a whole new way.

Not being an artist at all, I still found this fascinating. Thanks, Liz.

I so love your line work. And the draping! To die for!

Fascinating post. Been busy, so only just now got around to reading it.

Spiritually, I tend to call myself “agnostic” instead of “atheist” as is the style. I think there’s the possibility of experiences beyond our five senses and beyond the ability for science to explain. But, I think it’s equally obvious that most of us have no direct contact with an external divinity. If there is a higher power, it’s beyond our understanding.

But, perhaps we get glimpses of it. Or, maybe it’s all neuroscience. To the layperson, there’s not a whole lot of difference between those two. And for the creative mind, the line between them is as fuzzy as anything you can imagine.

I hope you’ll read Hallucinations, Brian. I am certain you’ll find it as utterly fascinating as I did. And after writing/deleting several other comments to your comment, I’m going to say “Let’s get together over a drink some time and have a long discussion…” 🙂

I need to get caught up on my Oliver Sacks reading. I haven’t yet cracked the covers of his book on music.

I had two hypnogogic dreams in recent memory. One I knew what it was as it was happening, so that the vague-faced “bogeyman” I could sense in the room was annoying rather than scary. I felt kind of resentful toward my brain for making it.

The other involved a group of goofy, costumed people gadding about outside the vacation cabin where I was staying. The walls had developed wide gaps between the boards through which I could see these ren-faire rejects spraying water and whooping it up. I knew they’d go away if I could pound on the wall, but I was paralysed and unable to move my arm.

Thanks for sharing, Stefan! Yeah, he refers to the music book in this one, and that’s going on my TBR pile also.